Research of Wari in the upper Moqugeua drainage has involved Peruvian and North American scholars for nearly three decades. Reportedly, Gary Vecelius excavated a test unit (~2 by 3 m) on the summit of Cerro Mejía, however at the time the site’s cultural affiliations were unknown. Later collaborators affiliated with Programma Contisuyo conducted informal survey in the region of Torata and made preliminary reports in a number of formats (e.g. references). Because of its location some early researchers thought Cerro Baúl was a Tiwanku fortress, however visits from researchers familiar with the Wari heartland identified the associated artifacts as Wari (see Lumbreras et al. 1982). Robert Feldman’s excavations in 1989 confirmed that Cerro Baúl was indeed affiliated with Wari. Moseley and Feldman described the Wari presence in Moquegua as a site unit intrusion and suggested that Moquegua might represent the furthest southern expansion of the Wari Empire (Feldman 1989; Moseley et al. 1991). The current program of research builds on these early foundations. Each season of research is briefly described below with links to more detailed information and publications resulting from each season. Summary information for a variety of topics can also be accessed using the sidebar.

Cerro Baúl as it appeared before the 2001 earthquake. This photo was taken from the road between Villa Cuajone and the lower entrance to SPCC.

In 1993, Michael Moseley, Robert Feldman, Johny Isla, and Ryan Williams mapped the surface remains on Cerro Baúl. The map they produced still forms the foundation of our present understanding of the layout of the site. Nevertheless the rock fall is very deep in some areas and excavations show that at times the surface remains can be misleading. The present map is only a guess at the arrangement of buildings on the summit of Baúl.

Cerro Petroglifo is located east of Cerro Mejía. The Wari canal runs along the south side of the hill. It can be seen on the left of this photo. The road that runs along the top and right of the photo was added in 1998. This photo was taken in 2004 by Ryan Williams. Since then the stone retaining walls of the agricultural fields on the south side of the hill have been cleared but the aquaduct and the canal are still intact.

The following year, over the course of the summer field season I studied the surface remains and made a sketch map of Cerro Petroglifo (AKA Cerro Sin Basura). In three days Ryan Williams and myself shot more than 1200 points documenting the architectural remains. For my master’s thesis I examined the spatial patterns of the site, the means of its construction, and its relationship to the other site’s in the colony as well as environmental conditions. It appears the site was never completed because building stone was piled in the western part of the hill, whereas stones marking the corners and subdivisions of larger spaces were visible in empty spaces on the extreme eastern end of the hill.

I shot this photo of Cerro Huayco while waiting for Ryan Williams to hike over to the site. I ran the laser transit and assisted Ryan Williams with the mapping of the agricultural system. In some cases we also mapped architectural remains. See Williams 1997. Cerro Huayco was occupied during the Late Intermediate Period and is attributed to the local Estuquiña.

In 1995 and 1996 I assisted Ryan Williams with his doctoral research, from which I gained a regional perspective. Moquegua from coast to puna has a number of vital resources and produces a wide variety of food stuffs in the vertically stacked ecological niches. Irrigation technology was an important determining factor in Wari colonization of the region. The Wari selected the tributary with the most water and an extensive canal system on the southern side of the river. Settlements were placed on hill tops and ridges overlooking the river and to the south on the other side of the canal (see 2006 Torata survey for more details).

I am on Cerro Baúl taking notes in unit 3b, a storage structure designed with an elevated wooden floor and a raised threshold. Wooden beams were set into the wall approximately 70 cm above a irregular humid clay floor. Artifacts were recovered from the surface layer and likely were deposited through looting activity. Near the floor we found remnants of burnt ichu grass- interpreted as roofing material or perhaps part of the elevated floor, as well as seeds from a cucurbit species and peanut shells.

Excavations in 1997 started small with four units in two different sectors of the site. I worked in sector C unit 3, and Gian Carlo Marconi excavated unit 6. Ryan Williams, Johny Isla, and Liz Klarich worked in two different structures of Sector B: Unit 5 the D-shaped structure and Unit 1, the brewery. Further information on this season of research can be found in Publications.

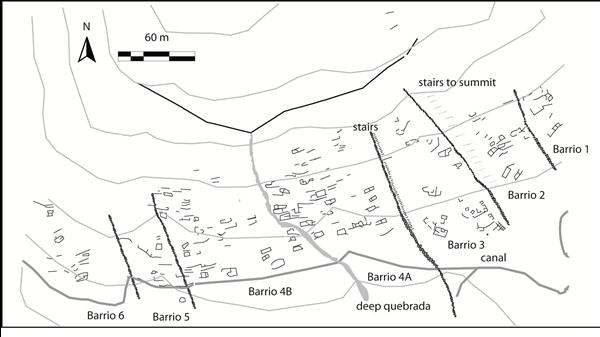

I mapped the southern slope of Cerro Mejía seen here in 1998 in preparation for my doctoral research focused on class distinction and power in the Wari colony of Moquegua. It was thought the lowest class in the colony would be represented by the modest dwellings on the slope of Mejía, however I now believe they were a lower middle class and that primary food producers must have occupied other smaller sites in the region.

In 1998 a number of research activities came together that would set the stage for later investigations. I worked on mapping the residential remains on the slopes of Cerro Mejía and Cerro Baúl, which included the residential remains identified as Sector G, El Tenedor, and the Baúl access path. On Cerro Baúl I excavated a small probe on the access path to gain a sense of the preservation and excavation requirements needed to work with the areas of modest residential remains. I also started a unit adjacent to Feldman’s 1989—Unit 2 on the summit of Cerro Baúl, which turned out to be a sizable midden on a lower terrace north of the palace in Sector A.

Unit 118 on the summit of Cerro Mejía includes several large plaza workspaces. In this picture you see Erick at the age of 9 helping mom out by taking soil chemical samples of an exposed floor surface. This is also the last year I used string. Between the wind and hungry rodents I have decided time is better spent excavating rather than repairing the string every morning.

Household Archaeology on Cerro Mejía started in 1999 and continued in 2000. The project opened more than 200 square meters, including 10 household units and 7 different buildings. This work revealed interesting patterns and essentially introduced new questions that remain primary to the current program of research. I examined the activities and resources available to the different residents and noticed that from house to house there was little consistency in the material culture in use. Initially I thought these distinctions might be related to class or occupational difference but later realized they might be attributed to ethnic differences between neighborhoods. I returned to these questions in 2008.

We found Unit 9—a Wari style patio group—on Cerro Baúl filled with smashed pottery and other objects. As you can see from the picture, we spent a lot of time labeling bags. The white bags were used for pottery because many of the pieces were quite large. You can also see 1 liter soil samples, collected from each meter for botanical analysis. Originally I intended to compare the “Wari patio group” with households on Cerro Mejía as part of my dissertation, however I soon realized that the patio group was just one component of a much larger complex.

In 2001 and 2002 a number of structures were excavated on Cerro Baúl as part of an NSF funded project directed by Ryan Williams and Michael Moseley. I supervised the excavation of Unit 9, a Wari patio group and other components of an elite residential complex in Sector A. My goal was to compare an elite residence from Cerro Baúl with my sample of households from Cerro Mejía, however so many materials were recovered analysis at the same level of detail was not feasible at that time (see Publications for recent comparisons of the data). Given the expected size of the complex further work was needed to understand the activities taking place within this larger residential complex.

This photo was taken by Ryan Williams from a helicopter. You can see ongoing excavations taking place in Sector A—”the palace”—and the brewery in Sector B. If you look closely you can see Donna Nash standing in 40A and Sofía Chacaltana Cortez standing in 40C.

In 2004 excavations on Cerro Baúl were to examine the possible locales where Wari and Tiwanaku may have interacted. Areas of the elite residential compound, brewery and D-shaped temple complex in Sector C were targeted. In Sector A areas were opened to the west of Unit 9 (the Wari patio group) revealing a ceramic workshop (40A) and garden space (40C). 40B was a narrow corridor that lead from the entrance hall to 40E, which we excavated in 2007 (see Houses for a complete layout of the elite residence in Sector A).

Artifact analysis is an important aspect of the overall project. This small flake of obsidian from Unit 5 on Cerro Mejía is characteristic of the shape of many flakes from this small house. In fact most houses on Meíja have two or three flake shapes that dominate the household assemblage.

2005 was a season devoted to several types of lab analyses. In particular, an effort was made to examine materials from both Cerro Baúl and Cerro Mejía in the hopes of defining a typology for different artifact types. Nevertheless, what became apparent was the big differences between Cerro Baúl and Cerro Mejía when it came to common domestic goods. It was decided that a larger sample was needed from Cerro Mejía to understand why there was such a diversity of materials found at the site and why there were few similarities between Mejía and Baúl.

Hugo Flores Torres, excavator and agronomist (vivero), has a keen eye for archaeological features. Here he stands in front of a ridge top canal at the site of Las Peñas located on a ridge on the south bank of the Torata tributary up stream from Cerros Mejía and Baúl.

In 2006 with funding from the Curtiss T. and Mary G. Brennan Foundation I conducted a survey with the help of Kasia Szremski and Lindsey Realmoto. Using Bruce Owen’s (1996) systematic survey of Torata we visited sites located near the projected course of the Wari canal. Since we found so few decorated Wari sherds on Cerro Mejía I suspected that smaller Wari affiliated sites may have no decorated sherds on the surface and would not be identified as Middle Horizon occupations during the survey. Using architectural style, plainware pottery, and the presence of obsidian we believe we have identified ten small sites with materials similar to those on Cerro Mejía. Future test excavation and radiocarbon dating will be needed to verify the sites’ affiliation. During the survey I also noted important technological differences in canal construction between the Wari system and the later Estuquiña systems.

At the crossroads between Cerro Baúl and Cerro Mejía the town of Torata has erected a model of Cerro Baúl (in orange) topped with a bull that is harnessed by a golden chain. This image represents a local myth about Cerro Baúl in which a bull emerges from a crack in the summit when the moon is full and descends the hill to drink from the river. The goal is to find the bull and take its golden chain. Climbing the small Baúl one morning, which is much easier than the real one, the 2007 excavation crew pose for a photo. Cerro Meíja can be seen in the background. From left to right: Jim Meierhoff, Caleb Kestle, and Donna Nash.

In 2007, we returned to Cerro Baúl. With a grant from the Howard Heinz Endowment for Latin American Archaeology I returned to the elite residential complex or “palace” in Sector A to learn more about the ceramic production taking place in the open patios between the entrance hall and Unit 9 (the Wari patio group). I did not uncover an area where vessels were fired however, I did find an area were a sparkly-mica rich rock was being ground into temper and small pits filled with three different colors of mineral pigment. We also found the path through the palace that connected the entrance hall to Unit 9 and took an overhead photo mosaic of the entire palace complex.

The following year I shifted back to work on Cerro Mejía. The results from excavation in 1999 and 2000 uncovered a very diverse assemblage and since that time I had wondered what might account for the material variety we encountered. In 2008 we excavated two medium sized houses in barrio 4A on the southern slope of Cerro Mejía. It was our goal to enlarge the household sample in order to have a larger sample from which to conduct comprehensive analysis and gain a better understanding of the differences between the neighborhoods and houses within each neighborhood. I expected to have to log a great deal of lab and library time to tie any one neighbor hood to the origin of the people who colonized Cerro Mejía, however during the excavation we found the equivalent of a smoking gun. The project co-director, Monika Barrionuevo encountered a placa pintada in unit 17. It had been placed above a tomb beneath the latest floor surface.

Placa pintadas appear to be a type of offering made in association with burials as well as other ritual contexts. They have not been identified in Formative Period contexts within Moquegua despite a fairly extensive mortuary sample. Instead they are a common cultural feature of areas of the department of Arequipa in the Majes and Chuquibamba drainages, approximately 120 miles north of Moquegua (Nash and Barrionuevo 2009).

In 2009 we continued work on Cerro Mejía in barrio 3. each house fit within a 10 by 12 meter grid and were located close to one another so that we might examine the spaces between houses. Unfortunately the houses in this area of Mejía’s slope were more deeply buried than usual and excavation progressed slowly. Nevertheless once we reached the use surfaces we learned that both houses had more obsidian than we typically find with the wide diversity of cherts and substantial amount of obsidian debitage suggesting that people occupying Unit 19 were possibly specialists in the working of stone.

The majority of the obsidian found on Cerro Mejía is in the form of retouch flakes. These small waste products indicate that all households had at least one person that knew how to sharpen an obsidian tool, however only unit 19 has the larger waste products that can be associated with the regular production of bifaces and other types of obsidian tools.

During excavations in 2008 and 2009 we recovered materials from four houses. These materials were analyzed in 2010. Unfortunately we recovered few ceramic remains and still do not have a sufficient sample of pottery to understand the production and use of vessels on Cerro Mejía. Nevertheless, patterns of house design and construction, as well as the assemblages associated with each structure give us a clear picture of how activities and material culture varied from house to house.

This rustic face neck jar was found smashed on the floor of one of the patios in Unit 17, a structure with remains of clay clumps and possible mineral pigment that may have been used for ceramic production. While evidence remains sparse, current data supports the hypothesis that ceramics were produced by multiple households in a variety of forms and a range of styles. The ceramic assemblage is small and with future research we need to try to find midden deposits because few sherds were left behind in the houses upon abandonment.